Prohibition in the Foothills of the Blue Ridge: Stills, Violence and Women’s Political Power

Introduction

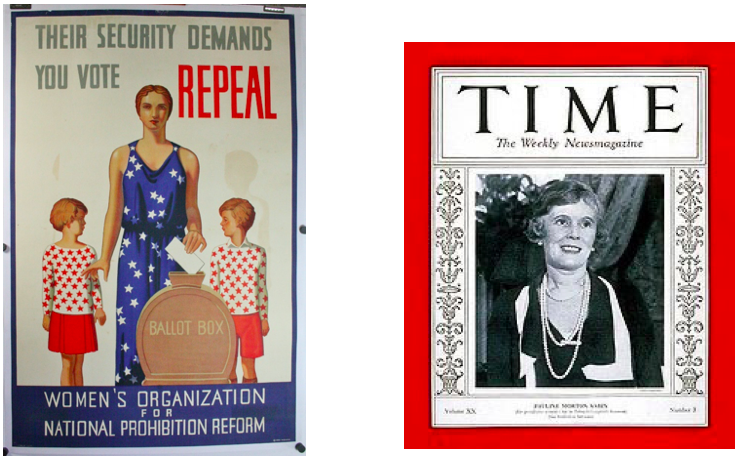

With this and similar posters the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) hoped to usher in a noble new world of national sobriety. Of course, what the WCTU and their allies actually ushered in was a world of violence, corruption, and crime.

Loudoun County, and the towns and villages in the foothills of Blue Ridge Mountains experienced the same spasms of moral righteousness, shattered hopes, violence, corruption, and the rise of women’s political power as the rest of the Country.

What many people do not realize is that prohibition – unintentionally — also ushered in a new world of political power for women in the United States.

The 18th amendment – prohibition – was ratified in January 1919. The 19th amendment – the right of women to vote — was ratified 20 months later in August 1920. That was not a coincidence.

Those that pushed so hard for a Constitutional amendment to outlaw liquor pushed equally hard for the right of women to vote thinking that it would guarantee the 18th amendment would never be repealed. In fact, it did the opposite. It empowered women to exercise the moral authority and the political courage to repeal of the 18th.

The WCTU in Loudoun County

Northern Virginia and Loudoun County had a long history with brewing and distilling before the prohibition era. In 1774 George Washington signed a deed allowing John Mercer to operate a distillery as a part of his mill in Aldie. By 1799 Washington had constructed his own distillery just three miles from his Mount Vernon estate and was producing 11,000 gallons of rye whiskey a year making it one of the largest distilleries in the Country and one of the most profitable components of his Mount Vernon plantation.

Between the late 18th century and early 20th, breweries, and distilleries flourished in Loudoun, Clarke, Warren, and Fauquier producing whiskey – generally rye – brandy and cider.

Between the late 18th century and early 20th, breweries, and distilleries flourished in Loudoun, Clarke, Warren, and Fauquier producing whiskey – generally rye – brandy and cider.

Despite the long history of liquor production in and around the Blue Ridge – or perhaps because of it – pro-prohibition groups were exceedingly active in in the early 20th century and were a major force in Virginia becoming a “dry” state. Prohibition became effective in the Commonwealth on Halloween 1916, three years before the 18th amendment was enacted.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was particularly strong in Loudoun County. The WCTU was founded in 1873 in Hillsboro, Ohio by Ms. Annie Wittenmyer. Despite its links with prohibition, the actual focus of the WCTU was temperance in all things in life – not just liquor. It strongly opposed the use of tobacco and advocated a vegetarian diet. It actively supported many humanitarian causes.

Local chapters of the WCTU were called unions. While unions worked closely with the state and national organizations, they were largely autonomous and could choose to work for reforms that would be most beneficial in their local communities.

Loudoun County was home to several WCTU unions. The Lincoln WCTU was founded in 1878 (the first local union in Virginia), the Young Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of Hamilton in 1894, and the Purcellville WCTU in 1913. The Lincoln WCTU was the most active union in Loudoun County, and it remained active until 1965.

The President of the Virginia Chapter of WCTU from its founding in 1898 until 1938 was Mrs. Sarah Hoge of Lincoln. During that period, she grew the statewide WTCU membership from fewer than 1,000 to close to 11,000.

The WCTU was not the only pro-prohibition force active in Loudoun County. During this period Mrs. Hoge’s husband, Howard M. Hoge was President of the Prohibition and Evangelical Association of Loudoun County. He was also a minister of the Society of Friends at Lincoln.

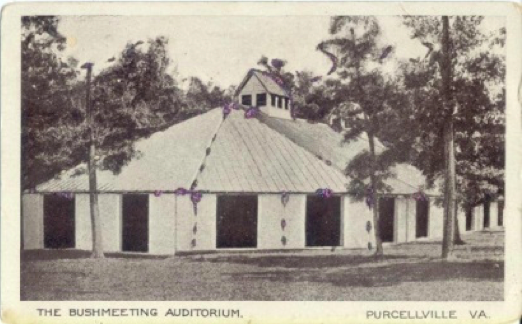

Beginning in 1894, Mr. Hoge and the Association organized a yearly temperance rally, known as a bush meeting in Purcellville. Each summer thousands of people gathered near the Purcellville train station to participate in a multi-day rally with the intend of outlawing the production and consumption of liquor. Over a period of years, the Purcellville rally became the largest such event in Virginia.

Photograph from Northern Virginia History Notes: Purcellville Bush Meeting Auditorium Now Purcellville Roller Rink Purcellville, VA Built 1903

According to a monograph prepared by Debbie Robison December 12, 2009 and published by Northern Virginia History Notes:

“Thousands of people came to the bush meetings in Purcellville. Crowd estimates were often in the range of 5,000 to 10,000 visitors. Many came by train from Washington, D. C. In 1894, it cost $1.55 round trip to take the train from D.C. to Purcellville. Special rates and excursion trains were provided for the event each year. People also came on horseback, in buggies and carriages, and by stage. It was quite a novel sight to see from 1,000 to 1,500 horses gathered in bunches beneath the oak trees, and carriages and farm wagons covering acres of land. Each wagon formed the center of a group of excursionists, and here the meals were served between speaking sessions. Food is known to have included an array of cold chicken, pie, preserves and homemade delicacies of various sorts. Tents were brought for overnight camping; however, if these were unavailable, the farmer and his wife slept in their wagon. Meetings lasted from a few days to a week or more.

In 1894, gatekeepers began collecting an entrance fee of 5 cents for each person over the age of 15 years. The fee offset the costs of the event, including that years’ purchase of a 9,600 square foot circus tent that was erected within a clearing.”

National Prohibition

On January 16, 1919 Nebraska became the 36th state to ratify the 18th amendment and the rest of the County began the “Noble Experiment” that Virginia had begun 3 years earlier. The experiment did not go as planned.

As an interesting footnote, the 18th outlawed the production, transportation, and sale of liquor not possession or consumption. Some wealthy individuals and private clubs were able to purchase sufficient supplies before prohibition became effective to legally serve cocktails to their guests and patrons throughout the 14 years before prohibition was repealed. Supposedly one could always enjoy a legal cocktail as a house guest of Franklin D. Roosevelt during those “dry” years.

Well before prohibition many farm families on the Blue Ridge, Short Hill, or Bull Run Mountains operated small distilleries for their own needs and to sell to friends and neighbors. Now some of these entrepreneurs grew much larger to meet a growing demand.

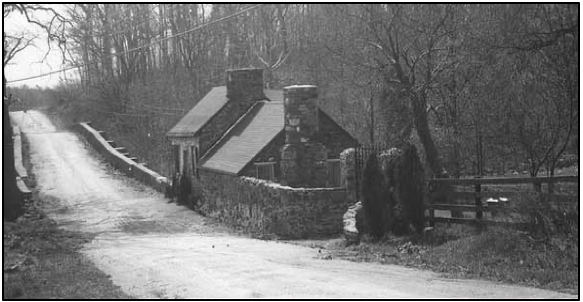

According to an excellent article: Mountains Full of Moonshine by Eugene Scheel published by Loudounhistory.org a favorite location for selling the local product was the Broad Run Tollhouse which can still be glimpsed as one crosses Broad Run on Route 7 near the Dulles Town Mall.

Before the tolls were removed in 1924, every car and wagon crossing the one lane bridge had to stop and pay the toll. If by chance a thirsty traveler wanted to pay an extra $2 it just might be possible to find a pint jar to help smooth the journey. An extra $8 or $9 would bring a full gallon of refreshment.

During World War I two Loudoun entrepreneurs – Lertie Holsinger and Amos Jenkins sold bootleg liquor from the Broad Run Tollhouse

On the ridge above Bluemont, an entrepreneur named Jess Tomblin made a strong corn whiskey and stronger apple brandy. So many people complained to Leesburg Judge J.R.H. Alexander about the business that the judge was forced to send the sheriff to investigate. However, as the Judge himself was a frequent and loyal customer of Mr. Tomblin he warned Tomblin before the raid to only have a few gallons on hand. The fine would then be about $10 and the business could continue with minor interruption. According to Mr. Scheel’s article Mr. Tomblin’s business continued to operate into the early 1940s.

Of course, there were murders. On the early morning of August 29, 1931 Lertie Holsinger shot his partner at the Broad Run Toll House 78-year-old Amos Jenkins. According to an October 2020 article in Ashburn Magazine by Mathew Annis: “During the trial for the toll house shooting, Holsinger claimed he was awakened by sounds outside and looked out the window to see Jenkins taking the ax from a woodpile while muttering threats against him. Jenkins allegedly made his way upstairs to Holsinger’s room, pushed his way inside, and brushed aside Holsinger’s attempt at self-defense. At this point Holsinger said he snatched his gun — a .22 pistol — from the bedside drawer and shot Jenkins twice. Jenkins stumbled from the house to the side of the turnpike, where he collapsed to the ground.”

The only witness to the shooting was the housekeeper Janie Shugars, her testimony substantiated Holsinger’s story. The jury duly found Holsinger innocent of murder.

“According to records in historic archives, Holsinger subsequently divorced his wife and married Janie Shugars, the very same housekeeper whose testimony had exonerated him. Shugars passed away in 1942 from an accidental gunshot wound, at the age of 43. Holsinger remarried three months later to a local teenager named Minnie Snider, and moved to Maryland, where he died in 1969 at the age of 75.”

A federal agent was killed in a raid at a distillery on the banks of the Goose Creek between Evergreen Mills Road and Route 15. The still was operated by “Old Man” Quesenberry who was sentenced to 27 years by Judge JRH Alexander. Apparently Judge Alexander did not mind enjoying Mr. Tomblin’s product but frowned upon shooting federal agents.

A Leesburg based IRS agent, Jay Lambert, was shot while raiding a still in the forests at Belmont Plantation in Ashburn.

The End of prohibition

The corruption and violence that accompanied prohibition in Loudoun and surrounding Counties was seen all across the Country and magnified many times over in the cities.

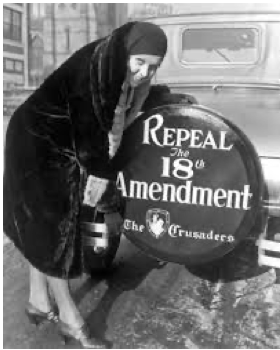

Why was the 18th amendment repealed? To say that it did not work is a necessary but not sufficient answer. Over the years as the violence grew many organizations were formed to try to repeal the 18th.

One of the most powerful and successful was the Woman’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR) formed by Mrs. Pauline Sabine in 1929 in Chicago.

Mrs. Sabine was a wealthy, socially prominent, politically well-connected heir to the Morton Salt Company fortune. She had been an early supporter of prohibition. “I felt I should approve of it because it would help my two sons. The word-pictures of the agitators carried me away. I thought a world without liquor would be a beautiful world. “

However, with time and experience she grew to oppose prohibition strongly and aggressively. She focused on four issues:

- ¨ Hypocrisy of politicians

- ¨ Ineffectiveness of the law

- ¨ Decline of temperate drinking

- ¨ Growing prestige of bootleggers

Her testimony before the House Judiciary Committee includes an excellent summation of her concerns and the concerns of growing numbers of mothers across the country.

In pre-prohibition days, mothers had little fear in regard to the saloon as far as their children were concerned. A saloon keeper’s license was revoked if he were caught selling liquor to minors. Today in any speakeasy in the United States you can find boys and girls in their teens drinking liquor and this situation has become so acute that the mothers of the country feel something must be done to protect their children.

In other testimony she pointed out that the Prohibition movement hoped to eliminate the liquor industry. In fact, what it had done was de-regulate and de-tax the industry. “What did we think would happen? Of course! Without regulations and without taxes the industry would become more profitable and grow.”

In the first two years after its founding, the WONPR grew to 1.5 million members – triple the membership of the WCTU. And many of the members of the WONPER were wealthy, socially prominent, and politically active.

On December 5, 1933 Ohio became the 34th State to ratify the 21st amendment thus repealing nationwide prohibition.

WONPR was only one of many national and local organizations to actively oppose prohibition. However, its opposition was a highly significant factor in providing the moral justification of women, particularly mothers to support repeal.

The irony is that WTCU and many other groups supported the right of women to vote solely to assure that prohibition would never be repealed. The women’s vote was a significant factor in electing Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Democrats in the 1932 election and the adoption of the 21st amendment in 1933.

Today

Today – a little more than century after we began the “Nobel Experiment” — many good people in and around the Blue Ridge make their living – legally — producing, selling, and serving the wine, beer, whiskey, brandy, and cider that the WCTU and their allies outlawed.

Loudoun County is home to 44 of Virginia’s 280 wineries, the most of any County. Loudoun has 738 acres of vineyards producing 19% of Virginia’s wine grapes. The annual wine production in Loudoun is valued at $36 million.

Loudoun has 35 breweries and is one of the most vibrant craft beer destinations in the US.

The Catoctin Creek distillery was founded by Becky and Scott Harris in 2009 as the first legal distillery in Loudoun County since before Prohibition. Undoubtedly the award-winning rye produced today by Catoctin Creek is a far cry from the unaged, unbranded product of George Washington’s Mt Vernon distillery.

Of course, the problems of excess alcohol consumption that drove the prohibition movement a century ago have not disappeared. Today however in the US, in Virginia and here in the foothills of the Blue Ridge the causes of alcoholism are better understood than a century ago and the options for treatment and control are much more widely available.

And women in the US, in Virginia, and in the foothills of the Blue Ridge are exercising their 19th amendment rights with greater impact than ever before.

Author’s comment: Please note that our heroine in the first poster is vanquishing liquor while riding side saddle. This was, after all, 1918.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.