Changes in the Blue Ridge Forests: heat, weather, bugs, and people

Introduction

Over the past months several Happenings articles have delt with the benefits of trees for both the environment and for our human health. Trees are the major source of the oxygen we breath; absorb the carbon dioxide that is a big component of the greenhouse gases warming the climate and filter our water. Trees are natural sponges, collecting and filtering rainfall and releasing it slowly into streams and rivers, and are the most effective land cover for maintenance of water quality.

Looking out our windows at the Blue Ridge Mountains or driving along the pretty, and historic rural roads of Western Loudoun County it is easy to believe that the forests we see have been with us for generations and will stay with us, unchanged for generations to come.

That is a dangerously false and simplistic view. The forests are and have always been dynamic systems constantly evolving. However, it is very probable that several factors are combining to accelerate the rate of change for today’s forests.

With this article we look at some of those factors with the idea that an appreciation of the forces of change can help mitigate the worst impacts and benefit from any positive impacts.

The Blue Ridge Mountain forests that we see today are different in many ways from the forests through which Commander Mosby and his raiders rode during the Civil War.

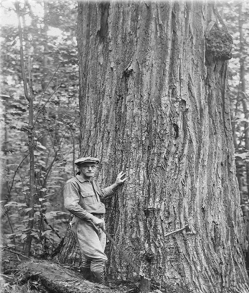

In the 1860’s Virginia’s mountain forests were characterized by large stands of mature trees included chestnut, hemlock, and many varieties of oak. Commercial logging in the early 20th century took the biggest, tallest trees – namely the oaks – through clear-cutting. The oaks, which are fire and drought tolerant have greatly decreased. The loss of oaks reverberates throughout the local environment. More than 200 species of organisms depend on oaks at some point in the life cycles, for food, shelter, and shade.

One of the ways the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service is working to increase oak regeneration, as well as reduce fuel load to prevent massive fires, is through controlled burns to reduce forest density and open up the canopy to allow for oak regeneration and other species.

It is not just the oaks that have declined in Virginia. In the August 6, 2020 edition of Happenings, we discussed the efforts of the Nature Conservancy VA to restore longleaf pine forest to Virginia. Friends of the Blue Ridge Mountains (FBRM) contributed 600 trees to that effort. One focus of the Nature Conservancy’s programs in Virginia is to restore healthy and climate resilient forests by increasing diversity.

One dramatic change in the forest environment throughout the entire east coast has been the loss of the American chestnut. The American chestnut was considered one of the most important forest trees throughout its range and the finest chestnut tree in the world.

However, the species was devastated by chestnut blight, a fungal disease that came from introduced chestnut trees from East Asia. It is estimated that between 3 and 4 billion American chestnut trees were destroyed in the first half of the 20th century by blight after its initial discovery in 1904.

In many areas the chestnut has been replaced with less fire tolerant species – meaning they burn more easily – such as red maple and yellow poplar.

Climate Change

In November 2018, the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) released the fourth National Climate Assessment Report. The USGCRP is a collaboration of thirteen federal agencies including Agriculture, Commerce, Interior, EPA, the Smithsonian, and Defense created by Congress.

The Report contains some scary stuff about the potential for drastic changes in the way forests – including the forests in and around our portion of the Blue Ridge will look and function over the coming decades.

According to a summary published by the Citizens-Times of Ashville, N.C. as the earth warms, due to increases of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, drought will increase, leading to larger, more intense fires and outbreaks of tree-damaging insects. Climate change will also lead to more extreme storms and an increase in rain and flooding, leading to runoff and stream pollution and a decrease in water quality.

Directly quoting the report:

“Earth’s climate is now changing faster than at any point in the history of modern civilization, primarily as a result of human activities. The impacts of global climate change are already being felt in the United States and are projected to intensify in the future.

“The severity of future impacts will depend largely on actions taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to adapt to the changes that will occur.”

One of the key messages is that more frequent extreme weather events will “increase the frequency and magnitude of severe ecological disturbances … and will alter forest productivity and health and the distribution and abundance of species.”

We are fortunate in our immediate area that – to date — two of the biggest dangers associated with climate change – storms and forest fires – have not had the impact that they have had in other parts of the country.

Forest fires — With regard to the increased danger of forest fires the Citizens-Times article refers to Andy Tait, a registered forester with the EcoForesters which is a non-profit professional forestry organization headquartered in Ashville, NC. EcoForesters says its mission is to preserve and restore the Appalachian forests through education and stewardship. It works with private forest owners to manage their property for forest health and sustainability.

According to Tait the No. 1 concern he hears from clients and the public is the fear of wildfires burning their homes and their forests.

“People are afraid. It’s a very natural, human instinct,” Tait said. “Although we do not have the high-risk level they have in the West, it should be a consideration for people on where they’re building homes.”

Because global temperatures are rising, and the air gets drier the higher up in elevation, Tait said building on mountaintops surrounded by dry timber is not the best practice.

“If you build down in the bottom of a cove forest, it’s moister and better for building. Fires burn uphill. Those higher, drier forest are more likely to burn, especially on ridge tops,” he said.

Using fire-wise practices can also help mitigate the impact of climate change in forests, he said, including the types of building materials, keeping a 30-foot buffer free from vegetation and flammable materials such as firewood, around your home, and employing the right landscaping.

“Some trees are more flammable than others. Rhododendron and mountain laurel have greatly increased their range and density, but they are not fire tolerant. They burn readily, and they’re used heavily in landscaping,” Tait said.

Better landscape choices are buckeye, serviceberry, fruit trees, dogwoods, and paw paws, which have a low flammability rating, he said.

Vigilance is key, Tait said, since more than 90 percent of fires in the East are human caused, either through arson, careless campfires or brush burning that gets out of control.

“With an increase in drought, wildfires are probably not going to be natural fires, they’re going to be human-caused,” he said.

Storms – While storm severity has not yet increased dramatically in our area as a result of climate change, local governments throughout Northern Virginia have jointly taken a few steps to prepare for the worst. The Federal Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 created strong financial incentives for local governments to prepare risk assessment studies and develop disaster mitigation plans. Local governments throughout Northern Virginia including Loudoun County., Leesburg, Lovettsville, Purcellville, Round Hill, Middleburg and thirteen other jurisdictions participated in a study that produced the Northern Virginia Hazard Mitigation Plan of 2017.

The plan includes a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction analysis of the impact of various natural disasters including flooding, winter storms, wind, drought, earthquakes, sinkholes, tornadoes, and hurricanes. The document also includes jurisdiction specific steps to minimize the dangers and to mitigate the damages should such a disaster occur.

The plan was prepared in cooperation with both The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Virginia Division of Emergency Management (VDEM).

Not only does the Plan provide guidance for local government action pre and post disaster it smooths the process of local governments securing federal funding to help prepare for disasters and to recover from disasters that may occur.

Invasive Insects

The forces of change shaping our Blue Ridge Mountain forests are not limited to global warming. One of the more insidious is the invasion of insects.

Ash trees infested with emerald ash borer beetles along the Appalachian Trail. The loss of the outer grayish bark and exposure of the underlying, brighter-colored, orange bark is from woodpeckers chipping away at the outer bark while searching to feed on the ash borer beetles. This is referred to as “blonding,” and it is common on ash trees that have been killed by the emerald ash borer. Photo and text Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute

Researchers associated with the Smithsonian Institution have been documenting the impact of invasive species on forests for many years. According to a report published in Ecosystems the Smithsonian researchers determined that approximately 25% of tree deaths in a section of the Blue Ridge Mountains over the past 30 years were due to invasive bugs transported by humans.

A long article published in the May 2020 issue of Smithsonian Magazine quotes the lead author of the study, Kristina Anderson-Teixeira: “That’s pretty significant for the functioning of the forest. We’re losing cool species, species that we value for one reason or the other.” Normally trees have mortality rates of 1 or 2 percent per year, she says. For the trees that invasive species impacted, the figure was as high as 20 percent.

Changes to the forest affect the animals that live in them. “There are these cascading impacts of the forest composition on. . . the forest animals,” Anderson-Teixeira says. For example, the gypsy moth, an invasive insect, has devastated oak tree populations in the area, and animals such as American black bears, white-tailed deer, Allegheny woodrats, Eastern gray squirrels, and southern flying squirrels rely on acorns from those trees.

“Due to these invasive species,” says William McShea, a wildlife ecologist with the Conservation Ecology Center at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) and one of the study’s 20 authors, “you’re getting a lot more young trees, and that’s a much different forest composition. That benefits some species and doesn’t benefit others.” White-tailed deer flourish with young vegetation and woody plants at the forest floor, for example. But other species, including birds, prefer a more mature forest. Of course, an abundance of white-tailed deer is itself a threat to the forest.

Invasive bugs are not a new problem for the Blue Ridge forests. As previously mentioned, chestnut trees once accounted for a quarter of the Eastern forest. But they were wiped out by the 1950s by an Asian fungus brought here on Japanese nursery stock.

According to a 2009 article by Peter Alsop in Smithsonian Magazine, a shipment of logs from Europe in 1931 introduced Dutch elm disease, another fungal blight, which infected elms across the Northeast. The European gypsy moth, let loose in Massachusetts in the 1860s, has ravaged oaks and other trees, and the hemlock woolly adelgid, an Asian insect introduced to the East Coast in 1951, has caused widespread mortality in hemlocks. Another invasive Asian beetle, the emerald ash borer, is destroying millions of ash trees in Virginia and throughout the Mid-Atlantic.

The cumulative effect of these and other pests and pathogens is a more homogenous forest, and one that is more vulnerable to invasion.

Invasive species impact the trees through different means. For example, the emerald ash borer, an insect, gets under the bark and disrupts the xylem, a tissue that brings water and dissolved minerals from the roots to the leaves. Gypsy moths cause leaves to fall off trees.

Even native species, such as white-tailed deer, which are in high density in certain parts of Shenandoah National Park, can disrupt the balance of the ecosystem if not regulated. As Anderson-Teixeira puts it, “There’s a lot of pressures on forests these days.”

The hemlock woolly adelgid, an insect native to East Asia, feeds by sucking sap from hemlock and spruce trees. It has decimated hemlock populations in Shenandoah National Park and beyond. Photo and text Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute

Invasive plants are also a threat to the Blue Ridge forests. The Blue Ridge PRISM (Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management) is a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to reducing the negative impact of invasive plants on the health of the natural and agricultural environment in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

According to PRISM publications, effective invasive plant control is a community and neighborhood issue because these aggressive plants know no boundaries – flowing water, birds, hikers, vehicles, and animals scatter and spread their seeds like a contagious disease. Steps can be taken to eradicate invasive plants from a park or private property only to have the area rapidly become reinfested from neighboring land. Community-wide action is needed. Through cooperative action, the PRISM aims to enable people to reclaim the Blue Ridge region’s natural heritage and to become stewards of the lands that are our birthright. The Blue Ridge PRISM is a project of the Shenandoah National Park Trust, which is a nonprofit and the fiscal sponsor of the Blue Ridge PRISM.

Conclusion

For FBRM readers interested in following the overall health of Virginia’s forests The Virginia Department of Forestry (VDOF) annually publishes The Forest Health Review. VDOF monitors the Commonwealth for major forest health disturbances including insect pests, pathogens, invasive plants, and severe weather events.

According to the most recent edition of the Forest Health Review (January 2020) the staff investigated a novel approach to invasive plant control (page 4), documented increasing oak decline throughout the Commonwealth (page 11), incorporated new technology into their survey work (page 12), and continued to monitor the state for emerging and established invasive pests.

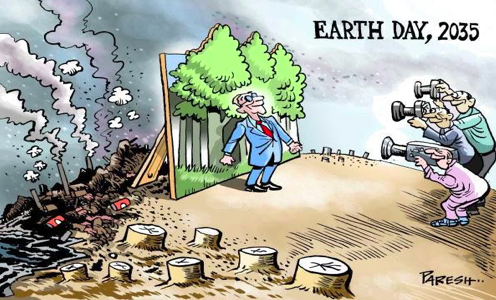

Despite all the pressures on Virginia’s forests brought by climate change, invasive insects, and invasive plants the biggest threat to our forests remains – PEOPLE.

According to the VDOF Virginia loses more than 16,000 acres of forest each year, mainly through conversion to home sites, shopping centers, roads, and other development. Rapid population growth places a demand on our shrinking forestland base. According to the Department of Forestry web site:

“Urbanization and development are the biggest factors in loss of forestland acreage. Since 2001, 484,965 acres of forested land has been lost to land use changes; 64% of this acreage were cleared for urban development.”

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.